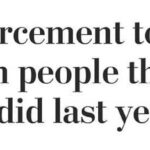

Police seize property and cash in questionable raids

Michigan laws allow police to seize assets even when no criminal charges are filed.

Study says Michigan is among the worst in protecting citizens from unlawful seizures by police.

Police defend seizing homes%2C cash%2C cars%2C insist forfeitures help fight crime%2C stop drug trafficking.

State%2C federal lawmakers introducing new bills to curb %22abusive%22 property seizures by police.

Thomas Williams was alone that November morning in 2013 when police raided his rural St. Joseph County home, wearing black masks, camouflage and holding guns at their sides. They broke down his front door with a battering ram.

Wladyslaw (Wally) Kowalski, 60, of Bloomingdale is fighting to keep his home in rural Van Buren County after police raided it in September and confiscated his marijuana plants.

“We think you’re dealing marijuana,” they told Williams, a 72-year-old, retired carpenter and cancer patient who is disabled and carries a medical marijuana card.

When he protested, they handcuffed him and left him on the living room floor as they ransacked his home, emptying drawers, rummaging through closets and surveying his grow room, where he was nourishing his 12 personal marijuana plants as allowed by law. Some had recently begun to die, so he had cloned them and had new seedlings, although they were not yet planted. That, police insisted, put him over the limit.

They did not charge Williams with a crime, though.

Instead, they took his Dodge Journey, $11,000 in cash from his home, his television, his cell phone, his shotgun and are attempting to take his Colon Township home. And they plan to keep the proceeds, auctioning off the property and putting the cash in police coffers.

More than a year later, he is still fighting to get his belongings back and to hang on to his house.

“I want to ask them, ‘Why? Why me?’ I gave them no reason to do this to me,” said Williams, who says he also suffers from glaucoma, a damaged disc in his back, and COPD, a lung disorder. “I’m out here minding my own business, and just wanted to be left alone.”

The seizure was allowed under Michigan’s Civil Asset Forfeiture laws, which allow police to take property from citizens if they suspect a crime was committed, even when there is not enough evidence to charge them. Homeowners like Williams have to prove they did not purchase their property with proceeds from criminal activity and then sue to get the property back.

Such laws are currently under attack nationwide by critics and legislators who say it is ripe for abuse. U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder announced earlier this month that he was tightening federal forfeiture laws to stop abuses. Michigan, with its own forfeiture laws, was ranked in a 2010 national study by a private, nonprofit group as among the worst in the nation for abuse.

“It’s straight up theft,” said Williams’ Kalamazoo attorney, Dan Grow. “The forfeiture penalty does not match the crime. It’s absurd. They grow an extra plant and suddenly they’re subjected to forfeiture. A lot of my practice is made up of these kinds of cases — middle-aged, middle-income people who have never been in trouble before. It’s all about the money.”

Police targeted Williams because he had been on the board of directors of a “compassion club” in Battle Creek, an hour away, and his name had turned up in records in a raid there, Grow said, even though he had not been involved with the club since 2011. The seizure, Grow contends, was particularly vicious.

“He is disabled and lives alone. They took the man’s cell phone and his car, and left him out there alone. He doesn’t have a landline. He was stranded out there for three days until somebody stopped by.”

The agency that conducted the raid, the Southwestern Enforcement Team, operated by the Michigan State Police, declined to discuss the case, except to say forfeitures are an important tool in fighting crime.

That team, which operates in southwest Michigan, seized $376,612 in cash and assets that year.

Not enough safeguards

The seizures in southwest Michigan were just a fraction of the at least $24.3 million in property and cash Michigan law enforcement seized from residents in 2013. The police agencies used those seized assets to buy equipment, train officers and beef up task forces.

“Michigan’s asset forfeiture program saves taxpayers money and deprives drug criminals of cash and property,” Col. Kriste Kibbey Etue, the director of the Michigan State Police, said in her last annual report to the governor and legislators on forfeiture revenue. “Michigan’s law enforcement community has done an outstanding job of stripping drug dealers of illicit gain and utilizing those proceeds to expand and enhance drug enforcement efforts to protect our citizens.”

But others say there are not enough safeguards to prevent abuses. They say there is an inherent conflict of interest because police agencies profit from the assets they seize.

“These forfeitures set off fundamental constitutional alarm bells,” said Democratic state Rep. Jeff Irwin of Ann Arbor. “It’s a perversion of our right to due process.”

Irwin has drafted legislation, which he plans to introduce this spring, that would require a criminal conviction before assets can be seized.

Irwin said he has been working on asset forfeiture reform since he took office in 2010, motivated by “horror” stories he was hearing from constituents, many of them medical marijuana patients and growers.

“The police were breaking into caregivers’ homes, showing up in riot gear, with guns, and then walking off with all the stuff,” Irwin said. “And the homeowners were being told if you mess with us, we’re going to mess with you. If you want to escape without a charge, just shut up and walk away.”

Saginaw Township resident Ed Boyke says he was a victim of just such a “shakedown.”

The 69-year-old retiree from General Motors obtained a medical marijuana card to help with pinched nerves in his neck following brain surgeries to correct epilepsy and remove a tumor. He also obtained permits to grow for two other patients.

In April 2010, Saginaw County Sheriff’s deputies and Drug Enforcement Administration agents raided his home. The DEA left, but deputies took his 2008 car, $62 from his wallet, his wide-screen television, his two lawn mowers, a leaf blower, a dehumidifier, an air compressor, “and a bunch of other stuff, some of it junk, right out of my garage,” he said in a recent interview.

Police said he was 12 plants over his legal limit of 36 plants, plus another 30 or so in the process of being cloned, but with no root systems. Boyke, a father of four and a Vietnam veteran with no criminal history, said he had just started cloning new plants because recently licensed medical marijuana users had inquired whether they could become his clients. “I just wanted to make sure I would have the inventory.”

Like Williams in Van Buren County, Boyke was never charged with a crime. But police came the day after the raid, he said, and warned that if he didn’t give them $5,000 in cash, they would put a lien on his house. He drove to the credit union, got the cash and handed it over.

“I was afraid,” he said in his small ranch house on Duane, where he has lived for more than two decades. “I didn’t know what to do and I didn’t want to lose my house.”

Saginaw County Sheriff William Federspiel, who conducted the raid, said, “There are two sides to every story,” when contacted by the Detroit Free Press seeking records on the Boyke raid. He did not respond to subsequent calls.

The financial incentive

The idea of civil asset forfeiture, under which the government can seize private property even if a crime has not been committed, dates to the 17th Century and British Admiralty Law. Unable to prosecute absentee owners, the English used the law to seize ships containing contraband. The laws came over to America with the settlers but were seldom used.

The federal government and most states ramped up their civil forfeiture laws in the 1980s as part of the War on Drugs, targeting drug kingpins. But over the years, the laws have been used to target citizens accused, but not charged, with minor drug trafficking, soliciting prostitution, money laundering, visiting an unlicensed facility to drink alcohol, and other crimes.

Michigan ranks among the worst when it comes to protecting innocent people from government forfeiture, according to the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit public interest law firm based in Arlington, Va., that fights unfair seizures. The firm commissioned a study of all 50 states in 2010 and ranked Michigan among the five most likely to abuse forfeitures, giving the state a “D-” grade.

“Michigan has two primary problems,” said Scott Bullock, a senior attorney at the institute. “First off, the government’s burden is very light, but the primary problem in Michigan is the direct and perverse financial incentive at the heart of the laws.”

Bullock said the federal asset forfeiture laws have been used to abuse Michigan residents as well.

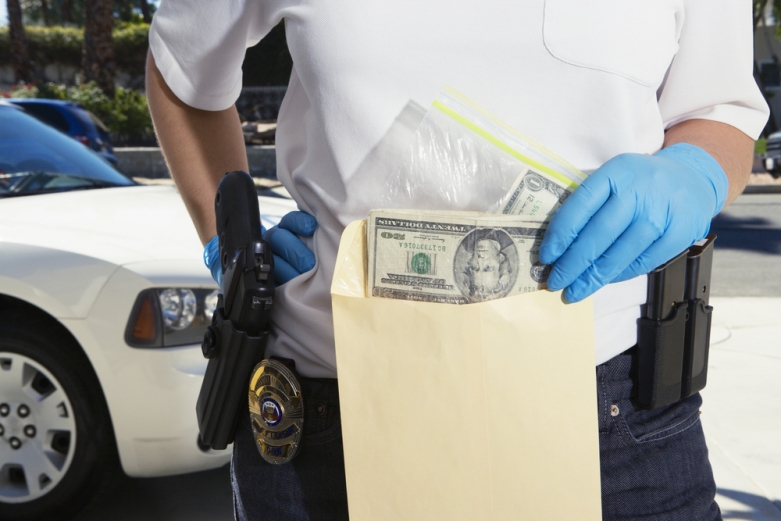

The institute most recently represented Terry Dehko and his daughter Sandy Thomas, owners of Schott’s market in Fraser. The family has owned the business since 1978 and made frequent cash deposits at a nearby bank to avoid keeping a lot of cash on hand. Their insurance policy would cover only $10,000 in the event of theft or robbery.

The federal government requires that banks report cash transactions over $10,000 as a means of detecting money laundering, and it is illegal to structure cash deposits to avoid this requirement. Despite a government audit of the store’s books in 2012 that showed no violations, federal agents seized $35,000 from Dehko’s bank account in January 2013.

The seizure nearly devastated the business, with the Dehko family struggling to make payroll and pay vendors. The Institute of Justice sued the government on behalf of the Dehko family, and amid wide publicity, the Internal Revenue Service agreed to return the money in November 2013, nine months later.

Dehko told the Detroit Free Press earlier this month the experience forever traumatized his family, and that he was putting the business up for sale.

“I worry all the time it’s going to happen again, that they’re going to fire back at me,” he said. “I’ll sell the business, but I’ll keep fighting for what’s right, for justice. The laws have to change.”

The Dehkos’ plight caught the attention of U.S. Rep. Tim Walberg, a Republican representing Michigan’s 7th District. Walberg has been leading the charge to change federal forfeiture laws, which, like state laws, allow the seizure of property even when there are no criminal charges levied.

Earlier this month, Walberg teamed up with U.S. Sen. Rand Paul, a Republican from Kentucky, to draft new legislation to revamp federal forfeiture laws and provide greater protections against abusive seizures. The law, which is receiving bipartisan support, would prohibit law enforcement from receiving proceeds from forfeitures and would, instead, require that the money go into the general fund.

And it would require that police show by “clear and convincing evidence” that a crime was committed, as opposed to the much lower standard of a “preponderance of evidence.”

“The Dehko case was egregious,” Walberg said in a recent interview. “This is not how forfeiture laws are supposed to work. I want to make sure innocent people don’t get hurt by these laws.”

The rules invite abuse

Michigan’s civil forfeiture practices have caught the attention of both civil rights and libertarian groups nationwide.

“There are a number of bad anecdotes coming out of Michigan,” said Andrew Kloster, who studies civil forfeitures nationwide for the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank for which he serves as a fellow. “And I think when there is smoke, there is fire.”

Michigan’s practice of handing over all forfeiture proceeds to the very police agency that seized them sets the scene for abuse, he said.

“If you get to keep the money you seized, that gives you the incentive to seize for the wrong reason,” he said, “and you’ll put your thumb on the scale. If your job is informally reliant on how much you bring in, you’re going to have an incentive to cut corners and seize as much as you can.”

Among the cases tracked by the Heritage Foundation: Krista Vaughn of Detroit was working for the American Red Cross in 2004 when she dropped a fellow worker off at a local bank and promised to swing back around and pick her friend up once the friend finished her banking. They were both wearing their Red Cross badges, according to published reports.

A Detroit police squad working on prostitution in the area determined that Vaughn’s friend was “making eye contact” with motorists in an attempt to solicit them.

Police ticketed the friend and confiscated Vaughn’s 2003 Sebring, claiming that it was being used as part of a prostitution ring. They eventually dropped the charges against her friend, but Vaughn had to pay $1,800 in fines, towing and repairs to her car in order to get it back.

The American Civil Liberties Union has intervened in Michigan cases as well. In 2008, a Detroit Police Department SWAT team, dressed in black and with guns drawn, raided the city’s Museum of Contemporary Art, where 130 patrons were celebrating Funk Night, a well-attended monthly party of dancing, drinking and art gazing. The patrons were forced to the ground and, in some cases, purses were searched. All of the patrons were issued tickets for “loitering in a place of illegal occupation,” because the museum had failed to get a permit to serve alcohol.

Then police began confiscating their cars, having them towed away under the city’s “nuisance abatement” program and insisting that patrons pay $900 apiece to get them back. The ACLU filed suit and the city agreed to drop the criminal charges but refused to return the cars.

The ACLU filed a second suit in 2010, demanding that the cars be returned, and U.S. District Judge Victoria Roberts agreed in 2012, noting that illegal search and seizures were a “widespread practice” and a “custom” of the Detroit Police Department.

Citizens at a disadvantage

Citizens doing battle with police agencies over forfeitures face distinct disadvantages. Among the worries: If the property owner complains too loudly, or hires an attorney, a criminal charge may follow.

Wladyslaw Kowalski, 60, with a PhD in engineering from Penn State, specializing in ultraviolet light technology, obtained a medical marijuana card for a heart condition, and immediately became fascinated by the process of growing superior strains of marijuana, devising intricate light systems in his 170-year-old farmhouse in rural Bloomingdale in southwest Michigan.

He became licensed to provide marijuana to other patients and began supplying for free two terminal cancer patients who lived locally.

He then began experimenting growing the plants outside in a large, fenced garden, using complicated light reflectors to extend the growing season by several weeks. “I basically created the same environmental conditions as southern California,” he said. “The plants just grew and grew.”

A police helicopter spotted the garden from above, and police raided the farmhouse in September. They cited him for failing to keep a cover on the garden, for it being visible from the road, and for having too much marijuana on the premises.

Kowalski said he was growing extra plants to ensure that he and his three clients would have adequate supplies throughout the year. “I’m dealing with a shorter growing season than if I was growing indoors. This is a math issue.”

Police froze his bank accounts and destroyed his plants but did not arrest him at the time.

Three months later, he shared his plight with the Mackinac Center, which posted an article online about it. Hours later, Kowalski was arrested and charged with two felony counts of drug manufacturing and a misdemeanor charge of giving marijuana away for free. And police have filed paperwork to take away the 20-acre farm, which has been in his family for more than 50 years. A trial date has not been set. If convicted, he faces up to seven years in prison.

“I was interested in the technology, that’s all,” he said. “I never made money selling marijuana and never planned to. I was going to make money introducing this new technology. And now I may lose everything.”

Contact L.L. Brasier: 248-858-2262 or [email protected]

Cashing in on forfeitures

Civil asset forfeitures are big business for police agencies in Michigan. Of the 635 law enforcement agencies in the state, 277 reported seizing citizens’ assets worth $24.3 million in 2013. The assets included homes, commercial property, cash, guns and other items.

Among those agencies with the biggest hauls in 2013:

Wayne County: Sheriff $633,893, other police agencies $6,052,871

Macomb County: Sheriff $158,832, other police agencies $2,717,538

Oakland County: Sheriff $361,163, other police agencies $1,402,635

Ingham County: Sheriff, $16,596, other police agencies $2,394,212

Kent County: Sheriff, $666,897, other police agencies $427,664

Source: Michigan State Police

![854081161001_5616033620001_5616024865001-vs[1]](https://ruccilaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/854081161001_5616033620001_5616024865001-vs1.jpg)

![100485780-100485780-bernie-madoff-looking-down-getty_r[1]](https://ruccilaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/100485780-100485780-bernie-madoff-looking-down-getty_r1.jpg)