These states let police take and keep your stuff even if you haven’t committed a crime

The policy that allows this is known as “civil forfeiture” — and it’s totally legal in most states.

By German [email protected]@vox.com Updated Sep 30, 2016, 9:15am EDT

Share this story

Share this on Facebook (opens in new window)

Share this on Twitter (opens in new window)

SHARE

All sharing options

Most states in America let police take and keep your stuff without convicting you of a crime.

These states fully allow what’s known as “civil forfeiture”: Police officers can seize someone’s property without proving the person was guilty of a crime; they just need probable cause to believe the assets are being used as part of criminal activity, typically drug trafficking.

Police can then absorb the value of this property — be it cash, cars, guns, or something else — as profit, either through state programs or under a federal program known as Equitable Sharing, which lets local and state police get up to 80 percent of the value of what they seize as money for their departments.

RELATEDWhy police could seize a college student’s life savings without charging him for a crime

So police not only can seize people’s property without proving involvement in a crime, but they have a financial incentive to do so. It’s the latter that state restrictions on civil forfeiture attempt to limit: Police should still be able to seize property as evidence.

But the restrictions in some states, such as California and New Mexico, make it so they can’t keep that property without a criminal conviction under many circumstances, under state law. And, therefore, they won’t be able to take people’s property as easily for personal profit.

The limits on civil forfeiture vary from state to state — but federal law leaves a loophole

A minority of states limit most or all forfeiture cases in different ways.

For example, in New Mexico and North Carolina, a court must convict the suspect of a crime before the same judge or jury can consider whether seized property can be absorbed by the state. In Minnesota and Montana, meanwhile, a suspect must be convicted of a crime in court before the seized property can be absorbed by the state through separate litigation in civil court. And in California, the state requires a conviction for forfeiture — but only to financial seizures worth up to $40,000; a boat, airplane, or vehicle; and any real estate.

These limitations don’t entirely stop police from seizing someone’s property. Cops can still do that with probable cause alone, and hold the property as evidence for trial.

But the government won’t be able to absorb the property and its proceeds without convicting the suspect of a crime. This limits police seizures in two ways: It forces cops to show the suspect was actually involved in a crime after the property is seized, and it can deter future unfounded seizures for profit since police know they’ll need to prove a crime.

But Lee McGrath, legislative counsel for the Institute for Justice, a national nonprofit that opposes civil forfeiture, said that police in most states with restrictions on civil forfeiture can still work with federal law enforcement officials to take people’s property without charging them with a crime. Only California, New Mexico, and Nebraska limit local and state police departments’ ability to work with the federal government in forfeiture cases.

Some state laws also don’t let police agencies absorb proceeds from forfeitures into their own budgets, instead directing the funds to the general budget. This helps remove the personal financial incentive police have to take and keep someone’s property.

But there’s another loophole through the federal law: If local and state cops work through the federal forfeiture program, they can still conduct forfeitures, and their police departments can keep as much as 80 percent of the proceeds — regardless of what state law says.

Despite the loopholes made available through the federal law, groups like the Institute for Justice have praised states for taking steps to limit civil forfeiture — a policy that has long been mired by criticisms and horror stories of police abuse.

The civil forfeiture reforms came in response to criticisms — and stories of police abuse

Critics have long argued that civil forfeiture allows law enforcement to essentially police for profit, since many of the proceeds from seizures can go back to police departments. People can get their property back through court challenges, but these cases can often be very expensive and take months or years.

The Washington Post’s Michael Sallah, Robert O’Harrow, and Steven Rich uncovered several stories in which people were pulled over while driving with cash and had their money taken despite little to no proof of a crime. The suspects in these cases were only able to get their property back after lengthy, costly court battles in which they showed they weren’t guilty of anything.

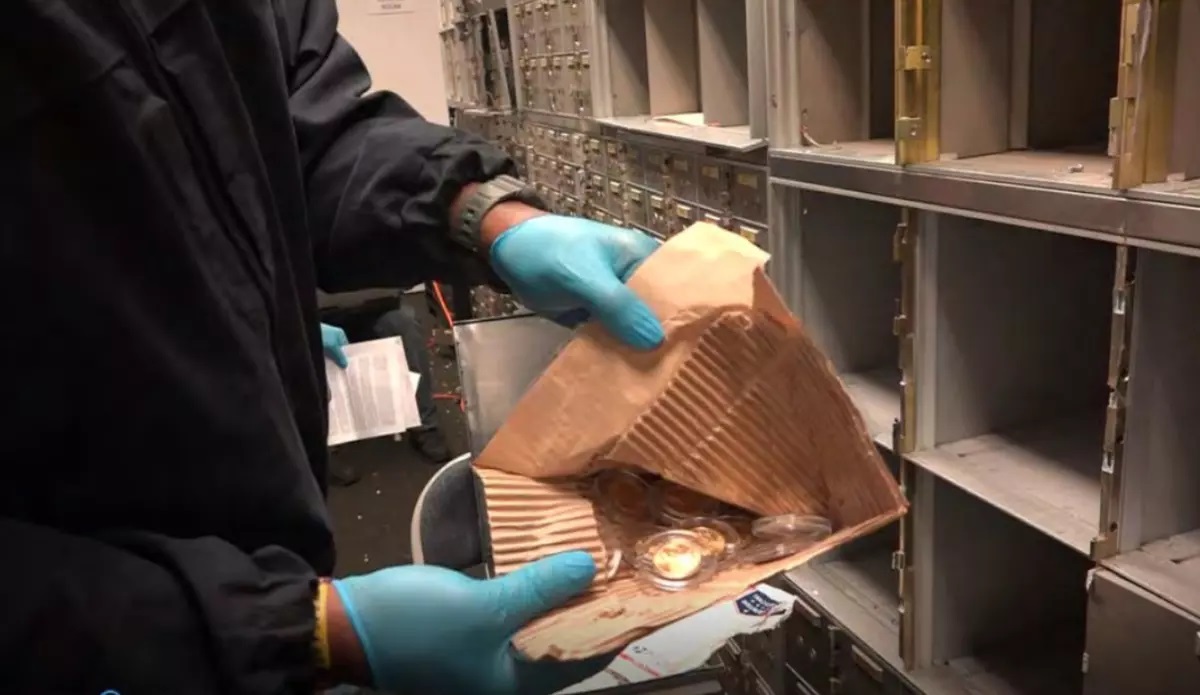

I’ve also covered the story of college student Charles Clarke, who was at the airport when police took his life savings of $11,000. Police said they smelled marijuana on Clarke’s bags — but they never proved the money was linked to crime, and Clarke provided documents that showed at least some of the money came from past jobs and government benefits. The Institute for Justice, which is involved in Clarke’s case, estimated that 13 different police agencies sought a cut of Clarke’s money.

It’s stories like Clarke’s that have driven some states to enact reforms. But the federal government and most states still fully allow civil forfeiture.

“It’s ridiculous. I think it needs to change,” Clarke told me in 2015. “I don’t think the cops should be allowed to take somebody’s money if they haven’t committed any crime. We’re treating innocent people like criminals.”

![103975804-GettyImages-608933126[1]](https://ruccilaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/103975804-GettyImages-6089331261.jpg)